Small Moves

I first saw the film Contact on a bootleg VHS copy at a friend’s house, when I was 14. It had been dubbed from a DVD to a tape that wasn’t long enough to contain the entire film. So during one of the most climactic moments, about 20 minutes before the end, it just flickered into a wave of distortion and… stopped. Cut to static.

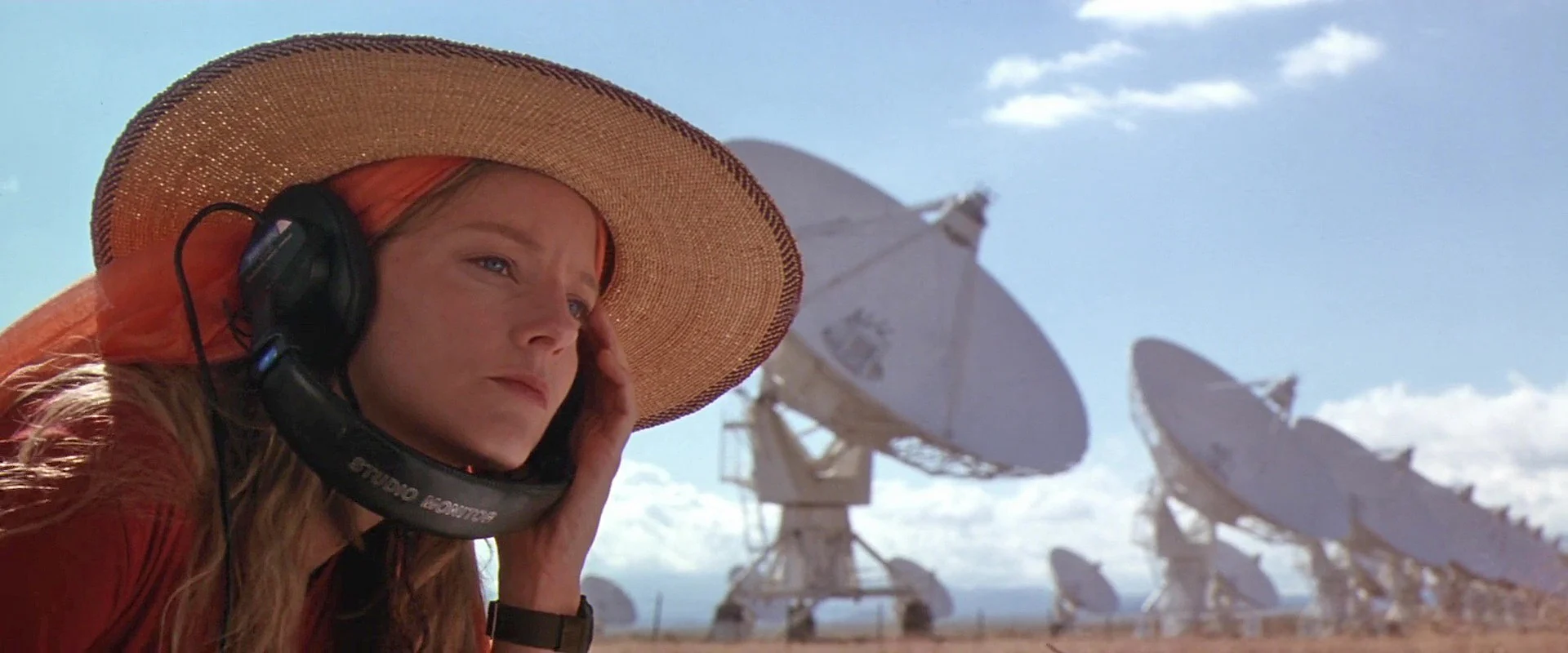

I sat there stunned, suspended mid-transmission. It felt especially surreal because the film itself is built on moments like that. The story follows Dr. Ellie Arroway, a brilliant astronomer played by Jodie Foster, driven by a lifelong focus on detecting signs of intelligent life beyond Earth. Her work is tedious, patient. Scientists in remote labs in Puerto Rico or New Mexico, listening to the sky, scanning for signals buried in the static. Partway through the film, when Ellie does pick up a pattern with clearly audible structure, there’s an abrupt loss of transmission—leaving Ellie and her team in a stunned silence. Later in the film, when the message has been decoded and used to build a machine, something goes terribly wrong during the live broadcast of its first trial run, and we watch through multiple security cameras as they, one by one, burst into static. Finally, when Ellie gets to travel through a wormhole, her video recording headset returns with zero proof, nothing but the patternless static itself.

And here I was, staring at my friend’s TV screen into that same gray noise: steady, relentless, unforgiving. I couldn’t finish the film. It took me another two weeks to track down a copy from the local video store. Once I did, I started again from the beginning, and by the time I finally reached the end of the 150 minutes—alone, lights dimmed, headphones on—it felt like something timeless had settled deep inside me. The delay didn’t dilute the experience, it intensified it. That unfinished first encounter mirrored the very longing Ellie Arroway carries through the film: a connection just out of reach, a message half-deciphered, the ache of unanswered questions.

Ever since, Contact has been my favorite film of all time. I consider it director Robert Zemeckis’s most mature and underrated film. It is a deliberately paced and expansive masterwork on wonder, grief, and purpose. It is about daring to ask the big questions simply for their own sake, but deriving profound meaning from them nonetheless. Scientist Carl Sagan wrote the novel in 1985 and didn’t live to see the completed film adaptation. He died during production in 1996, and in that sense, Contact isn’t just a film about Sagan’s ideas, it’s a vibrant and affectionate tribute to his inquisitive spirit. He wasn’t a man of blind faith, nor of rigid atheism. With Contact, he seemed to be exploring the liminal space in between, full of awe, admitting our limitations in humility before the cosmos.

Ellie’s journey follows a clear, mythic arc. On the surface, she’s embarked on SETI, the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence. But her real pursuit is far more intimate: she wants to prove that we are not alone. It is a question for humanity, but also for herself, deeply tied to the grief of growing up without her mother, then losing her father at age 9. The early scenes between young Ellie and her father are quiet and deeply moving, especially now that I have children of my own who stay up late asking questions about the planets in our solar system. That bond sets the emotional tone, and asks the fundamental questions for everything that follows. “Could we talk to Mom?” young Ellie asks, referring to the power of the ham radio she just used to contact someone in Pensacola, Florida. Her dad’s response is at once empirical and tender: “I don’t think even the biggest radio could reach that far.”

“Dad, do you think there’s people on other planets?” she later asks him. “I don’t know Sparks,” he answers. “But I guess I’d say, if it is just us, it seems like an awful waste of space.” It is a simple hypothesis, but teeming with implications about purpose and creation, human modesty and unbearable loneliness. This is especially effective because we are made to experience that overwhelming vastness of space during the film’s opening sequence, with a camera move starting on the surface of the Earth and flying all the way out to encompass billions of galaxies. This sequence lasts a full 3 minutes, with the final minute in complete silence. A bold choice for a mainstream film, with a visceral effect on those willing to sit through it: the realization of just how infinitesimally small we really are.

Throughout the film, Zemeckis continues to play the long game, pacing Ellie’s discoveries with the kind of restraint most sci-fi films are too impatient to attempt. When the signal comes, it’s not a bewildering spectacle—it’s math, sound waves, rudimentary puzzle pieces embedded in each other. The detection and decoding is laborious and painstaking, yet the film lets the scientific process be thrilling in its believability. The stakes in Contact aren’t built with threatening lasers and tentacles, but through the realism of humanity’s reaction to the unprecedented. The tension rises not through action sequences but through debate, discovery, and existential weight. Ellie’s primary antagonist, David Drumlin, represent the performative gatekeeping of scientific advancement. After undermining and defunding Ellie’s projects for years, Drumlin quickly reverses course as soon as a discovery is made, presenting it to the White House as if it were his own. And as Ellie’s discovery advances in prominence, tension rises through government interference, media frenzy, and theological debate. Moderates and fanatics alike begin to ask, “These scientists—are these the people you want talking to your God for you?”

At the heart of the film is the interplay between science and religion, and this theme is expressed through Ellie’s relationship with Palmer Joss (played by Matthew McConaughey). Author of a book called Losing Faith: The Search for Meaning in the Age of Reason, and later becoming the President’s religious advisor, Palmer serves as both Ellie’s love interest and ideological counterweight. Their chemistry is undeniable, and their debates are sharp, sincere and disarming. Embodied by Palmer and Ellie, faith and science aren’t enemies, but sparring partners. Their shared journey is symbolized beautifully by the compass that keeps passing between them, a literal and metaphorical guide. Palmer gives it to Ellie at the start of her journey, and when she returns it to him years later after he causes a rift between them, it’s his turn to find his way. What’s powerful is that both Ellie and Palmer have something to teach each other. She learns to make space for the existence of the unprovable. “Did you love your father?” Palmer asks her. “Prove it.” He, in turn, learns to see moral clarity not just in divinity, but in her scientific integrity. She’s the one who never compromises her principles, while he wavers from his. The compass they exchange thus becomes a token of guidance, trust, and the idea that they’re navigating different maps toward the same truth.

Stylistically, Contact belongs to a golden age of cinematic storytelling—an era where adventure films were allowed to be both technically daring and unabashedly heartfelt. Alan Silvestri’s score ties it all together. Bold, orchestral, unafraid of emotion. In an era when many modern soundtracks hide behind ambience, Contact wears its heart on its sleeve—but never loses control. Zemeckis, a master of this blend, carries the DNA of Back to the Future into Contact, but here, he applies those tools with restraint. There’s a calculated elegance to how the film moves, with his use of extended one-shots and impossible camera movements. These create a sense of omniscience, but not intrusion. There’s something spiritual in the way we’re invited to watch. Take the now-iconic medicine cabinet shot, where young Ellie races up the stairs and the camera enters a mirror with no visible cut. It’s not just a flex, it’s an unsettling visual metaphor that echoes the film’s deeper themes of reflection, recursion, and perception.

“Is it possible that it didn’t happen? Yes.” Ellie later testifies in a Congressional hearing about her interplanetary journey for which she lacks any evidence. “As a scientist, I must concede that, I must volunteer that.” Here she admits that reality isn’t a uniform broadcast, but a signal we interpret through belief, memory, and perspective. In the monologue that follows, the most heartfelt of Jodie Foster’s extraordinary performances in the film, Ellie reveals how she was transformed by her experience. Not because she found “truth,” but because she let go of needing it to come in a measurable form. Contact argues, subtly but firmly, that even the most rational minds need faith—not in opposition to science, but as the glue that holds conviction together when evidence is unobtainable through our limited human capacities.

Decades later, Contact still feels like the most honest take on first contact ever made. Not because it shows us what aliens might be, but because it shows us what we are: seekers. Doubters. Children tuning dials in the dark, hoping someone answers back.

“Small moves, Ellie. Small moves.”

These are the first words her father speaks to her in the film, as she’s still learning to use the radio. These words are later echoed when Ellie finally does make contact with intelligent life beyond Earth, and asks what’s supposed to happen next. That line has stayed with me, especially lately as I’ve gone through a season of personal trials and change. These words were a reminder to take it one day at a time. Proceed with humility and grace. Trust that the signal might be faint now, but will emerge from the static.

Just keep listening.